The Vajrayana path reveals to us the nature of reality, an experience that is understood and accessed through a variety of methods. Of these many methods, the stories, poems (dohas) and songs of realization of the “great accomplished ones” (mahasiddhas) are profound, paradoxical, and sometimes playful offerings into this experience. In the Vajrayana Virtual Retreat on June 6-12, as Lama Tsultrim and Dorje Lopön Charlotte share with us these stories, poems and songs, and as a sacred world comes into our view, we come to rest in our true nature.

Please enjoy below, an excerpt from Lama Tsultrim’s book Wisdom Rising: Journey into the Mandala of the Empowered Feminine, recounting the story of renowned mahasiddha, Naropa, followed by an excerpt from Tilopa’s Song To Naropa.

Join us for the Varjrayana retreat, beginning this Saturday. We will share in the opportunity to write our own songs and poems as we bring these teachings to life on our path. There will also be a brief introduction to Nejang or Tibetan Self-Healing Yoga as taught by Dr. Nida Chenagtsang. This retreat is required for those in the Magyu Program. Click here to register »

Excerpt from Wisdom Rising by Lama Tsultrim Allione

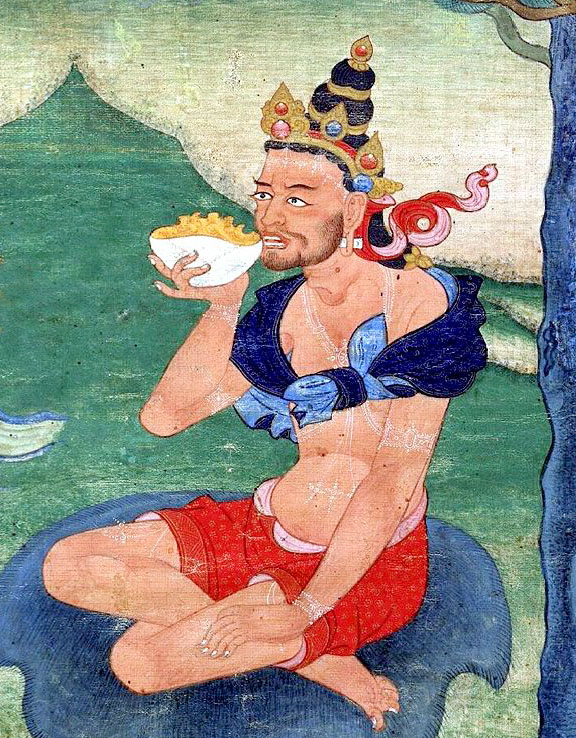

One of the first stories I read when I studied Tibetan Buddhism at nineteen was about the effect of an old hag dakini, who pulled the rug out from under a great scholar, Naropa (1016–1100), a teacher in the Tantric tradition in India. He became the abbot of the prestigious Buddhist University of Nalanda. He was a brilliant intellectual who had become a monk after renouncing his marriage, saying that his wife had faults.

One day he was sitting outside with his back to the sun, studying books on grammar, epistemology, and logic, when a terrifying shadow fell across the pages. Looking up, he saw an old hag. Because of his training in logic, he immediately analyzed thirty-seven ugly features:

She asked him if he understood what he was reading. When he said yes, she asked the key question: “Do you understand the words or the sense?” When he answered that he understood the words, she was delighted and began to dance, waving her stick in the air.

When Naropa saw this, he thought he would make her even happier and said, “I also understand the sense.” Hearing this, she began to cry and threw down her stick.

When he inquired why she was so upset, she responded, “I was happy because you told the truth when you said you understand the words, but sad when you said you also understand the sense because you lied!”

Then he asked, “Who understands the meaning?”

“My brother, Tilopa,” she answered, and disappeared into a rainbow.

She asked him the key question: “Do you understand the words or the sense?”

His impulse to analyze her thirty-seven ugly features shows that logos, words, and the intellect permeated his every encounter with the world, even one as immediate as this experience with the hag, this feminine presence, old and ugly because she was primordial, who yet could blow his cover. After this encounter, he felt like a phony and knew he must leave in order to find the meaning. His world was shaken to the core, his whole rigidified world shattered; he realized he had to find the embodied experience of what he had studied so long in theory. Indeed, he was so shocked by this encounter that he decided to leave his position as head of Nalanda, giving up his status and all his belongings and books, and announced his intention to seek a guru.

The entire administration and students of Nalanda University begged him to stay. But he told them it was useless to try to dissuade him. His answer to the monks and scholars was, “It must be,” and he took his begging bowl and staff and set forth on what was to be a torturous twelve-year journey to meet his guru, Tilopa. During this journey all his preconceptions had to be broken down until he had the direct unmitigated experience of reality. Because his conditioning was so thoroughly embedded in him, he had to go through great hardship and tests before he could actually see his guru. But his guru was always with him.

All his preconceptions had to be broken down until he had the direct unmitigated experience of reality.

Whenever Naropa made mistakes in his search for wisdom, which was often, the voice of his guru from the sky would say:

The mysterious home of the dakini.”

I have always loved this passage, which is repeated several times as he goes through the process of trying to find Tilopa. What is the “mirror of the mind” that is the “mysterious home of the dakini”?

This was the question that he was asked to contemplate again and again as he kept missing the point. For example, as he set out to look for his guru, he came upon a mangy dog full of maggots lying in the middle of the road. Naropa was so intent on his search that he jumped over it, and at that moment the dog disappeared into a rainbow in the sky, and he heard a voice that said:

The mysterious home of the dakini.

Without compassion you will never find the guru.” 2

The mind is like a mirror because the primordial state of sentient beings, the ground of being, is the unadulterated awareness. It is stainless because it is naturally pure from the beginningless beginning, everything unborn and unstained; this is mysterious because it’s beyond our conceptual mind. It does not judge, does not alter itself due to experiences. Nothing can sully it, although it can be obscured, just as the sun may be hidden behind clouds but never changes and is simply obscured temporarily.

Excerpt from Tilopa’s Song to Naropa

(From the book Mother of the Buddhas, by Lex Hixon)

Mahamudra, the royal way, is free from every word and sacred symbol.

For you alone, beloved Naropa, this wonderful song springs forth from Tilopa

as spontaneous friendship that never ends.

The completely open nature of all dimensions and events

is a rainbow always occurring yet never grasped.

The way of Mahamudra creates no closure.

No strenuous mental effort can encounter this wide open way.

The effortless freedom of awareness moves naturally along it.

As space is always freshly appearing and never filled,

so the mind is without limits and ever aware.

Gazing with sheer awareness into sheer awareness,

habitual, abstract structures melt into the fruitful springtime of Buddhahood.

White clouds that drift through blue sky, changing shape constantly,

have no root, no foundation, no dwelling;

nor do changing patterns of thought that float through the sky of mind.

When the formless expanse of awareness comes clearly into view,

obsession with thought forms ceases easily and naturally.

1) and 2) Wisdom Rising excerpt references: Herbert Guenther, transl., The Life and Teaching of Naropa (London: oxford university Press, 1963).

Header Photo: Bodhi Stroupe